LU Robots Replacing Humans in The Workforce Questions

On September 13, 2022, the New York Times published two articles:

· “Supply Chain Broke? Send The Robots” by Peter S. Goodman. This article describes efforts by employers to incorporate robots and other labor saving and labor replacing technology into the workplace.

· “Uber Will Pay New Jersey $100 million in Back Taxes” by Cade Metz. In this article, the state of New Jersey demanded back taxes from the ride-hailing company, claiming it misclassified drivers as independent contractors.

Read these two articles and answer the following questions:

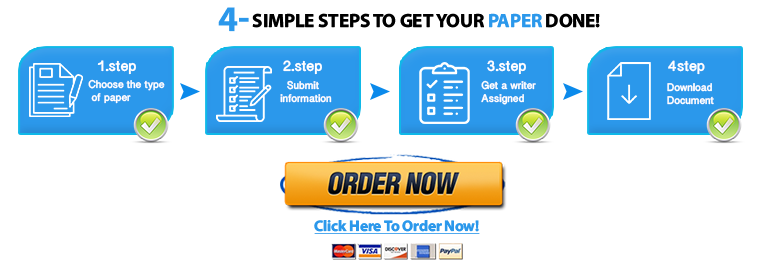

Taken together, how do the articles illustrate the growth oriented, technology dynamic, and crisis prone nature of contemporary capitalism? What are the drawbacks to employer efforts to incorporate more labor saving and labor replacing technology into the workplace? Why would a company like Uber want to classify its drivers as contractors rather than employees? Why would a company like Uber resist efforts by lawmakers and the courts to classify their drivers as employees? How do the actions of employers described in the two articles reflect the contradictions of capitalism?

Taken together, how do the two articles reflect the processes of bureaucratization, rationalization, and McDonaldization? How do the actions of employers described in the two articles reflect the irrationalities of bureaucratization, rationalization, and McDonaldization? Why would a government body fight a company’s efforts to classify workers as independent contracts and not as employees?

The companies behind e-commerce are embracing automation as the means of transcending the limitations of humans.

Locus Bots at Locus Robotics, a Massachusetts company that aims to automate warehouses with robots. Credit: Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Peter Goodman, who has covered the supply chain breakdown since 2020, reported this article from Philadelphia.

The people running companies that deliver all manner of products gathered in Philadelphia last week to sift through the lessons of the mayhem besieging the global supply chain. At the center of many proposed solutions: robots and other forms of automation.

On the showroom floor, robot manufacturers demonstrated their latest models, offering them as efficiency-enhancing augments to warehouse workers. Driverless trucks and drones commanded display space, advertising an unfolding era in which machinery will occupy a central place in bringing products to our homes.

The companies depicted their technology as a way to save money on workers and optimize scheduling, while breaking down resistance to a future centered on evolving forms of automation.

“It’s hard to get people motivated to do this work,” said Kary Zate, senior director of marketing communications at Locus Robotics, a leading manufacturer of autonomous mobile robots — carts that roll through warehouses, accompanying humans who select goods off shelves. “People don’t want to do those jobs.”

More than two years into the pandemic, persistent economic shocks have intensified traditional conflicts between employers and employees around the globe. Higher prices for energy, food and other goods — in part the result of enduring supply chain tangles — have prompted workers to demand higher wages, along with the right to continue working from home. Employers cite elevated costs for parts, raw materials and transportation in holding the line on pay, yielding a wave of strikes in countries like Britain.

The stakes are especially high for companies engaged in transporting goods. Their executives contend that the Great Supply Chain Disruption is largely the result of labor shortages. Ports are overwhelmed and retail shelves are short of goods because the supply chain has run out of people willing to drive trucks and move goods through warehouses, the argument goes.

Some labor experts challenge such claims, while reframing worker shortages as an unwillingness by employers to pay enough to attract the needed numbers of people.

“This shortage narrative is industry-lobbying rhetoric,” said Steve Viscelli, an economic sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania and author of “The Big Rig: Trucking and the Decline of the American Dream.” “There is no shortage of truck drivers. These are just really bad jobs.”

A day spent wandering the Home Delivery World trade show inside the Pennsylvania Convention Center revealed how supply chain companies are pursuing automation and flexible staffing as antidotes to rising wages. They are eager to embrace robots as an alternative to human workers. Robots never get sick, not even in a pandemic. They never stay home to attend to their children.

A large truck painted purple and white occupied a prime position on the showroom floor. It was a driverless delivery vehicle produced by Gatik, a Silicon Valley company that is running 30 of them between distribution centers and Walmart stores in Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas.

Trucks at Gatik’s facility in Fort Worth. The company displayed one of its driverless vehicles at the Home Delivery World trade show in Philadelphia. Credit: Cooper Neill/Reuters

Here was the fix to the difficulties of trucking firms in attracting and retaining drivers, said Richard Steiner, Gatik’s head of policy and communications.

“It’s not quite as appealing a profession as it once was,” he said. “We’re able to offer a solution to that trouble.”

Nearby, an Israeli start-up company, SafeMode, touted a means to limit the notoriously high turnover plaguing the trucking industry. The company has developed an app that monitors the actions of drivers — their speed, the abruptness of their braking, their fuel efficiency — while rewarding those who perform better than their peers.

The company’s founder and chief executive, Ido Levy, displayed data captured the previous day from a driver in Houston. The driver’s steady hand at the wheel had earned him an extra $8 — a cash bonus on top of the $250 he typically earns in a day.

“We really convey a success feeling every day,” Mr. Levy, 31, said. “That really encourages retention. We’re trying to make them feel that they are part of something.”

Mr. Levy conceived of the company with a professor at the M.I.T. Media Lab who tapped research on behavioral psychology and gamification (using elements of game playing to encourage participation).

So far, the SafeMode system has yielded savings of 4 percent on fuel while increasing retention by one-quarter, Mr. Levy said.

Another company, V-Track, based in Charlotte, N.C., employs a technology that is similar to SafeMode’s, also in an effort to dissuade truck drivers from switching jobs. The company places cameras in truck cabs to monitor drivers, alerting them when they are looking at their phones, driving too fast or not wearing their seatbelt.

Jim Becker, the company’s product manager, said many drivers had come to value the cameras as a means of protecting themselves against unwarranted accusations of malfeasance.

But what is the impact on retention if drivers chafe at being surveilled?

“Frustrations about increased surveillance, especially around in-cab cameras,” are a significant source of driver lament, said Max Farrell, co-founder and chief executive of WorkHound, which gathers real-time feedback.

Several companies on the show floor catered to trucking companies facing difficulties in hiring people to staff their dispatch centers. Their solution was moving such functions to countries where wages are lower.

The floor of the Pennsylvania Convention Center in Philadelphia during Home Delivery World.

Lean Solutions, based in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., sets up call centers in Colombia and Guatemala — a response to “the labor challenge in the U.S.,” said Hunter Bell, a company sales agent.

A Kentucky start-up, NS Talent Solutions, establishes dispatch operations in Mexico, at a saving of up to 40 percent compared with the United States.

“The pandemic has helped,” said Michael Bartlett, director of sales. “The world is now comfortable with remote staffing.”

Scores of businesses promoted services that recruit and vet part-time and temporary workers, offering a way for companies to ramp up as needed without having to commit to full-time employees.

Pruuvn, a start-up in Atlanta, sells a service that allows companies to eliminate employees who recruit and conduct background checks.

“It allows you to get rid of or replace multiple individuals,” the company’s chief executive, Bryan Hobbs, said during a presentation.

Another staffing firm, Veryable of Dallas, offered a platform to pair workers such as retirees and students seeking part-time, temporary stints with supply chain companies.

Jonathan Katz, the company’s regional partnerships manager for the Southeast, described temporary staffing as the way for smaller warehouses and distribution operations that lack the money to install robots to enhance their ability to adjust to swings in demand.

A drone company, Zipline, showed video of its equipment taking off behind a Walmart in Pea Ridge, Ark., dropping items like mayonnaise and even a birthday cake into the backyards of customers’ homes. Another company, DroneUp, trumpeted plans to set up similar services at 30 Walmart stores in Arkansas, Texas and Florida by the end of the year.

But the largest companies are the most focused on deploying robots.

Locus, the manufacturer, has already outfitted 200 warehouses globally with its robots, recently expanding into Europe and Australia.

Locus says its machines are meant not to replace workers but to complement them — a way to squeeze more productivity out of the same warehouse by relieving the humans of the need to push the carts.

A Zipline drone delivering medical supplies at a hospital in Rwanda in June.Credit…Luke Dray/Getty Images

But the company also presents its robots as the solution to worker shortages. Unlike workers, robots can be easily scaled up and cut back, eliminating the need to hire and train temporary employees, Melissa Valentine, director of retail global accounts at Locus, said during a panel discussion.

Locus even rents out its robots, allowing customers to add them and eliminate them as needed. Locus handles the maintenance.

Robots can “solve labor issues,” said Nathan Ray, director of distribution center operations at Albertsons, the grocery chain, who previously held executive roles at Amazon and Target. “You can find a solution that’s right for your budget. There’s just so many options out there.”

As Mr. Ray acknowledged, a key impediment to the more rapid deployment of automation is fear among workers that robots are a threat to their jobs. Once they realize that the robots are there not to replace them but merely to relieve them of physically taxing jobs like pushing carts, “it gets really fun,” Mr. Ray said. “They realize it’s kind of cool.”

Workers even give robots cute nicknames, he added.

But another panelist, Bruce Dzinski, director of transportation at Party City, a chain of party supply stores, presented robots as an alternative to higher pay.

“You couldn’t get labor, so you raised your wages to try to get people,” he said. “And then everybody else raised wages.”

Robots never demand a raise.

A Locus demonstration in 2017. The company’s robots are deployed in 200 warehouses around the world. Credit: Paul Marotta/Getty Images for TechCrunch

Peter S. Goodman is a global economics correspondent, based in New York. He was previously London-based European economics correspondent and national economics correspondent during the Great Recession. He has also worked at The Washington Post as Shanghai bureau chief. @petersgoodman

A version of this article appears in print on Sept. 13, 2022, Section B, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: Supply Chain Broke? Send The Robots.

Uber Agrees to Pay N.J. $100 Million in Dispute Over Drivers’ Employment Status.

New Jersey demanded back taxes from the ride-hailing company, claiming it misclassified drivers as independent contractors.

The payment will cover as many as 91,000 drivers who have worked in New Jersey in one of the years covered by the settlement. Credit: John Muggenborg for The New York Times

By Cade Metz

Uber has agreed to pay New Jersey $100 million in back taxes after the state said the ride-hailing company had misclassified its drivers as independent contractors.

An audit by the state’s Department of Labor and Workforce Development had found that Uber and a subsidiary, Raiser, owed four years of back taxes because they had classified drivers in the state as contractors rather than employees. On Monday, the department announced that Uber had paid the taxes with interest.

“Our efforts to combat worker misclassification in New Jersey are continuing to move forward,” Robert Asaro-Angelo, the department’s commissioner, said in an interview. “This shows that these workers in New Jersey are presumed to be employees. No matter what a company’s business model or what their technology is, workers have rights.”

The settlement would appear to be a retreat from the ride-hailing company’s repeated assertion that its drivers should not be classified as employees. Uber and other gig companies have for several years aggressively campaigned against efforts by lawmakers and the courts to classify their drivers as employees. But an Uber spokeswoman said in a statement that the company’s stance had not changed.

“Drivers in New Jersey and nationally are independent contractors who work when and where they want — an overwhelming amount do this kind of work because they value flexibility,” said Alix Anfang, the spokeswoman. “We look forward to working with policymakers to deliver benefits while preserving the flexibility drivers want.”

The New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development initially demanded payment of the back taxes from Uber in 2019, the first time a local government had sought back payroll taxes from the company. The move was a significant change in the way states treated the employment practices at the heart of “gig economy” companies like Uber.

In recent years, states and cities across the country have tried to rein in gig-economy companies that depend on inexpensive and independent labor. These efforts could reshape the business models of companies like Uber, but the legal landscape is far from settled.

California and Massachusetts have laws requiring that gig workers be designated as employees if certain criteria are met. Mr. Asaro-Angelo said those laws followed the lead of New Jersey, which has similar protections on the books.

In 2019, when the state first demanded that Uber pay back taxes for misclassifying drivers, it said that the company and Raiser, the subsidiary, owed far more than $100 million. An audit had uncovered that $530 million in back taxes had not been paid for unemployment and disability insurance from 2014 to 2018, according to news reports. The state also demanded $119 million in interest.

After Uber contested the department’s findings, the case was transferred to New Jersey’s Office of Administrative Law. Eventually, the company agreed to pay a revised figure and to drop its appeal.

The department now says that its initial audit was an estimate made without Uber’s cooperation. Relying on worker payroll data supplied by Uber, a subsequent audit assessed Uber and Raiser owed a combined $78 million in back taxes plus penalties and interest of $22 million.

The payment covers as many as 91,000 drivers who have worked in New Jersey in one of the years covered by the settlement. It will help provide benefits such as unemployment, temporary disability and family leave insurance.

Mr. Asaro-Angelo declined to say how the department would handle taxes that Uber may owe after 2018 or in the future. “Every year, it seems, the Legislature and the governor are passing new laws to make lives better for workers and give us more power to protect them,” he said.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!