Native Alaskan Short Responses, history homework help

In each of the following exercises, you will be asked to consider the evidence about ANCSA and Native corporations that was presented in this assignment. Based on that evidence, you will be asked to assess the validity of different conclusions. Be sure to respond to each question in one to two sentences, using proper grammar

1. Consider the following statement: The support of non-Native Alaskans was an important factor leading to the settlement of Alaska Native land claims. Is this conclusion consistent with the evidence presented in this learning block? Answer Yes or No, and then explain your choice in one or two sentences.

2. Consider the following statement: ANCSA was a fair settlement for Alaska Natives. Is this conclusion consistent with the evidence presented in this learning block? Answer Yes or No, and then explain your choice in one or two sentences.

3. Consider the following statement: ANCSA led to economic benefits for white Alaskans as well as for Natives. Is this conclusion consistent with the evidence presented in this learning block? Answer Yes or No, and then explain your choice in one or two sentences.

Land and Oil

In March 1867, Tsar Alexander II of Russia agreed to sell “Russian America” (quickly renamed the “Department of Alaska”) to the United States. Under the Treaty of Cession, the U.S. government paid the Tsar $7.2 million for a territory that comprised 586,412 square miles—roughly two cents an acre. (To see the text of the treaty, click here.)

Iñupiat with a Native skinboat, or umiak, 1935. (Click button for citation)

But who really owned all that land? At the time of the Alaska Purchase, Secretary of State William H. Seward estimated that the Native population of Alaska was slightly less than 60,000. (Seward, 1891) These Alaska Natives*—including the Inuit, Tlingit, Yupik, Haida, Aleut, and Iñupiat, among many others—claimed that the land had always been their home. Their aboriginal land claims* dated back well before American or even Russian ownership of the land.

Those land claims went unresolved for more than a century; the United States government claimed ownership of the vast majority of Alaskan land until the 1960s. In 1971, only about 1 million of the state’s 375 million acres were in private hands. (Turner, 1982). But, with Alaska so sparsely populated (especially in the vast Interior), and with little agriculture or commercial use for most Alaskan land, there were few conflicts over the Natives’ continued use of it. Most of Alaska was not suitable for settlement, in the same way that land in the Lower 48* was; for that reason, relatively few non-Natives were interested in the land. Congress in 1884 passed the Alaska Organic Act, which protected the Natives’ right to the “use and occupancy” of ancestral land, without addressing the question of whether the Natives actually owned it. (Jones, 1981)

Prudhoe Bay in 1968, the year oil was discovered there. (Click button for citation)

All that changed in 1968, when the Atlantic-Richfield Company discovered oil at Prudhoe Bay on Alaska’s Arctic Coast. It quickly became apparent that the most effective way to get crude oil from Prudhoe Bay to markets in the Lower 48 would be to build a pipeline to carry the oil to the port of Valdez in southern Alaska. (Banet 1991) But to build the pipeline, the oil companies would need clear title* to the land—land that was still subject to Native land claims.

It was a scenario that had played out so many times before in American history: land that for centuries had been used by Natives was, suddenly, extremely valuable to non-Natives. So many times before, that scenario had ended up with Natives being forced or cheated out of their land. But the outcome this time would be very different.

ANCSA and Native Corporations

Alaska was admitted to the Union as the 49th state on January 3, 1959. Under the terms of the Alaska Statehood Act, the federal government would transfer ownership of up to 104.5 million acres of land to the new state, but none of this would be land that was subject to Native claims. (Alaska Statehood Act, 1958. To read the law, click here. )

Former Alaska Governor Walter Hickel. (Click button for citation)

The law gave the state 25 years to select which tracts of land it wanted. In the 1960s, the state began to make its selections—but much of the land it wanted was subject to Native claims. Several Native groups filed lawsuits to stop the land selections, and the Alaska Federation of Natives* (AFN) was founded to advocate for a fair and comprehensive settlement to the land-claim issue. In response, the federal government shut down the selection process and told the state to negotiate an agreement with the Natives. (Jones, 1981)

The discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay in 1968 added urgency to those negotiations. Without a resolution of the Native claims, it would not be possible to build the massive Trans-Alaska Pipeline that the oil industry said was needed to carry Alaskan oil to markets in the Lower 48*. (Naske, 1994)

The pressure to come to a quick settlement in the interest of economic development was in fact reminiscent of the pressure to seize Native lands following the Georgia Gold Rush in the 1830s. In each case, the opportunity to extract a highly valuable natural resource suddenly made Native land even more valuable than before. But several factors helped to produce a very different outcome for the Alaska Natives:

- The Natives had effective political representation, through the AFN and other organizations;

- U.S. courts were more sympathetic to the Alaska Natives’ claims, ruling in their favor in several instances;

- The state government was willing to seek a negotiated settlement with the Natives;

- The federal government—including Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel, a former governor of Alaska—also favored a negotiated settlement; and

- Greater public awareness of the injustices done to Natives in the past increased the social and political pressure to find an equitable settlement. (Jones, 1981)

After protracted negotiations, Alaskan officials and the AFN reached an agreement in principle: Natives would receive land that they had historically used and drop their claims to any other land in the state in return for a cash settlement. The exact terms of that agreement would be for the federal government to decide and—after initially offering the Natives far less than they wanted, in terms of land and cash—Congress and President Richard Nixon eventually agreed to a historic deal.

A map of the original 12 Alaska Native regional corporations. A 13th regional corporation was established later. (click map to enlarge) (Click button for citation)

On December 18, 1971, President Nixon signed into law the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA*), which at the time was the largest land claim settlement in American history.

In return for letting the federal government “extinguish” their claims to most Alaskan land, Natives received 44 million acres and a cash payment of $962.5 million. The 44 million acres was one-ninth of the total area of the state of Alaska; the monetary settlement represented a direct payment of $462.5 million from the federal government and another $500 million to be paid over time from state oil revenues. (ANCSA, 1971)

Even more historic than the size of the ANCSA settlement was the way it was structured—a radical departure from the traditional model of Native reservations in the Lower 48, in which the federal government holds Native lands in trust. Instead of establishing reservations ANCSA set up a system of Native corporations* to administer the land and invest the monetary settlement for the benefit of Natives. (Thomas, 1986)

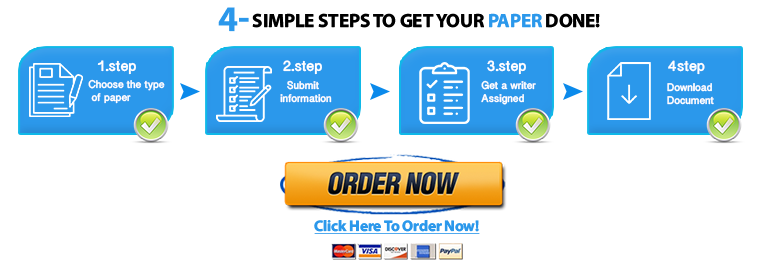

The law set up 12 regional corporations, each associated with a particular part of the state and the Natives who traditionally lived there. All Natives who were alive in 1971 could enroll in one of the corporations, and each received 100 shares of stock in the corporation in which they enrolled. (A 13th corporation was established later, for Natives who were not living in Alaska in 1971). The law also established more than 200 local or “village” corporations, in which Natives could also enroll and receive shares of stock. The corporations were given free rein to use the land and any mineral or other natural resources it might hold to develop for-profit businesses and to pay Native shareholders a yearly dividend based on those profits.

The corporation structure was the brainchild of the AFN, which saw this proposal as an opportunity to extend “the transformational power of capitalism…to Alaska Natives,” while also preserving the land and cash settlement so that it could benefit future generations. (Linxwiler, 2007)

A Tlingit totem pole in Sitka, Alaska. Click on the image to go to the Smithsonian’s Alaska Native Collections. (Click button for citation)

ANCSA was generally well-received in Alaska by both Natives and non-Natives. After years of legal wrangling over exactly who was entitled to Native corporation shares, many of those corporations have grown into successful businesses that generate substantial dividends and provide thousands of jobs for Native shareholders. And, by removing one critical barrier to construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, ANCSA paved the way for the emergence of the state’s “oil economy,” which has generated substantial economic benefits for both Natives and non-Natives. (Alaska Humanities Forum, 2016)

One unique aspect of Alaska’s “oil economy” is the Alaska Permanent Fund, a state fund that collects 25 percent of all oil-land royalties and invests those funds for the benefit of all Alaskans. The Fund, which in 2015 amounted to more than $51 billion, pays a yearly dividend to every qualified Alaskan; in 2015, that meant a dividend check of $2,072 for virtually every man, woman, and child in the state. (Klint and Doogan, 2015) By enabling construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, ANCSA in a very real sense made the Permanent Fund, and its yearly dividend checks, possible.

Still, the law remains controversial, especially among Natives who believe it weakens ties to Native heritage. (Thomas, 1985) Almost a half-century after its passage, the jury is still out on whether ANCSA was a “good deal” or a “raw deal” for Natives. But it is, in almost every respect, a very different sort of deal than that received by any other group of Natives in American history.